Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

Bug bounty hunting and penetration testing both focus on identifying security vulnerabilities, but they differ in structure, income stability, and career path. Bug bounty hunting offers flexibility and performance-based rewards, allowing individuals to work independently and earn based on the vulnerabilities they discover. Penetration testing, in contrast, provides structured work, fixed income, and long-term career growth through employment or contracted engagements.

Both paths depend on a solid understanding of web security, networking, and common vulnerabilities like XSS, SQL injection, and access control problems. Technical knowledge, along with the ability to learn more, experience, and strong writing skills in the form of clear and useful security reports, are all required to be successful in either role.

Enroll in Entri’s AI-Powered Cybersecurity course now!

What Is Bug Bounty Hunting?

Bug bounty hunting consists of digging through live websites, mobile apps, APIs, cloud setups, and anything else that a company makes available online that it openly asks people to test for security problems. These programs are run by big corporations like Google, Apple, Microsoft, Meta, and many banks, online stores and even government agencies – some free to join, others private and invite only for experienced hunters.

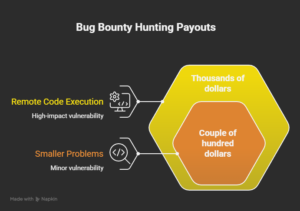

If you do detect a vulnerability, you make a good report detailing exactly where you found it, why it matters, how bad it could be if left alone, and what the company should do about it. If you report a problem that is new and has scope, they reward you according to the magnitude of the problem: some smaller problems will fetch a couple of hundred dollars, while a full remote code execution that could have someone take over servers could fetch thousands of dollars – or in rare cases even more.

Most hunters do this completely on their own, usually from home or somewhere that has decent internet service, and they set their own schedules at will. You choose the programs that make you laugh, you decide how long you want to spend bug hunting in each program, and you stop whenever you want without giving a response.

What Is Penetration Testing?

Penetration testing—most people just call it pen testing—is a paid, organized service where skilled security pros get hired to pretend they are real attackers and try to break into a company’s networks, web apps, cloud setups, APIs, mobile apps, or even physical hardware if that is part of the deal. The whole point is to uncover flaws that criminals could use so the organization can patch them up before anything bad happens.

As opposed to bug hunters, who go in and out of public programs on their own, pen testers almost always sign contracts that specify exactly what they can touch, how long they have, what methods are not allowed, and what legal protection the client gives them so they don’t get in trouble for doing their job.

A typical pen test follows a normal sequence of planning and scoping with client in order to understand their objectives and risks, reconnaissance to sketch out the surrounding quietly, scanning to see what ports and services are open, attempting to gain that first foothold, pushing deeper, increasing access and wandering around the network, and finally putting everything together into a complete report. The report is not a list of bugs, but proof such as screenshots and logs, clearly measured severity from a business perspective, and step-by-step recommendations for fixing what could actually be used by both tech teams and managers. Clients are from everywhere: big corporations, banks, hospitals, power companies, defense contractors and government offices who are obliged to comply with GDPR, PCI DSS, HIPAA or SOC 2.

Key Differences Between Bug Bounty and Penetration Testing

Bug bounty hunters are just like penetration testers, they both look for the same kinds of security holes, but almost every detail about their way of working, how they get paid, and what they do with organizations separates them. Hunters usually do fly solo, or share targets freely in groups online, then pick targets from thousands of open programs and decide on their own rules in the program’s rules; pen testers sign explicit contracts upfront stating what kind of assets they can test, when, how many methods are allowed, and what to do if something goes wrong. An hunter writes a brief and detailed report on one particular vulnerability, which is paid only when accepted as unique and valuable, while the pen tester writes a long, professional report on the full test duration, and is paid for doing everything in it, even though they find nothing earth shattering.

Money works very differently too. Bug bounties are all about variable, find-based rewards: you might grind for a month and earn nothing, then hit one monster bug and make more in a day than some people see in a quarter. Pen testing brings steady paychecks—either a reliable salary in a full-time role or agreed project fees—so you know roughly what is coming in each month. Hunters can jump into programs anywhere in the world without resumes or interviews as long as they follow the rules, but they battle heavy competition and the chance their hard work gets dismissed as a duplicate. Pen testers build relationships with fewer clients over time, sometimes turning one-off jobs into repeat business, though they usually need to go through hiring processes, prove credentials, and occasionally travel for hands-on work at a client’s site.

Skills Required for Each Path

Both careers rest on the same strong base: deep knowledge of how web apps work, common attack types like XSS, SQL injection, SSRF, and IDOR, network basics, reconnaissance tricks, and ways to actually exploit flaws when you find them. Tools like Burp Suite for intercepting traffic, Nmap for mapping networks, Metasploit for quick exploits, Nuclei for fast scans, Wireshark for packet analysis, and scripting in Python or Bash show up in almost every serious hunter’s or tester’s toolkit. On top of the tech side, bug bounty hunters lean hard into creative thinking, stubborn persistence when chasing edge cases, and the knack for noticing tiny misconfigurations that scanners skip.

They must also write clear, brief reports that prove the bug without wasting the triage team’s time, and they must learn constantly because new frameworks, cloud services, and patterning of attacks all appear—reading others’ posts online, joining live streams of talks, and breaking things in personal labs are part of the routine.

Income, Job Stability, and Growth Comparison

Bug bounty earnings swing wildly depending on skill, time put in, luck, and which programs you target. The top hunters—the ones consistently landing critical bugs—can clear well over $200,000 a year and sometimes push much higher during hot streaks, especially on private invites or high-payout programs from tech giants. Mid-level hunters who treat it seriously often land between $20,000 and $80,000 annually, while beginners and casual participants frequently see $0–$10,000 in their first year or two. There are no automatic benefits, no paid sick days, no employer-matched retirement, and you pay for your own gear, tool licenses, courses, and taxes out of pocket. The ceiling is basically unlimited if you get really good and build a reputation, but dry periods where reports get rejected or duplicated can hurt cash flow hard.

Which Career Path Should You Choose?

If you love calling your own shots, get energy from working whenever inspiration hits, and can handle stretches without income while chasing the chance for big scores, bug bounty hunting lines up well. It lets you build real, battle-tested skills fast, get noticed in the community through public reports, and experiment without needing anyone’s approval. The downside is the uncertainty, so it works best if you have savings to bridge quiet months or start it as a side project alongside something steady.

If steady money, a clear routine, teamwork, benefits, and a roadmap for promotions feel more important, penetration testing tends to deliver that smoother ride. You get predictable pay to cover bills and family needs, structured projects that teach you depth, and chances to move up into leadership or specialized roles over time. Many people dip into bug bounties first to gain confidence and proof of ability, then use those wins to land pen-testing positions where the pay and security are more reliable.

Enroll in Entri’s AI-Powered Cybersecurity course now!

Final Thoughts

Bug Bounty vs Penetration Testing, for example, provides you two very solid and respected ways to convert cybersecurity knowledge into a good career that pays well and actually protects people and companies. Hunting brings the euphoria of freedom, the freedom of discovery, and the potential for potentially lifechanging single payouts. Penetration testing also gives reliability, professional development, support to the team, and the satisfaction of accomplishing full and concrete security improvements.

There is no way to be perfect or “better”; it’s your decision to choose the path that works best for you and what you need right now in life. Embark on the action and start practicing right now: open an account on a bounty platform, take part in free labs, read real reports, break things safely, and keep up the pace. The need for good people in this field is only growing, and effort in either direction will take you farther than you might think at the moment.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between bug bounty hunting and penetration testing?

The main difference is in how the work is structured and paid. Bug bounty hunters work independently and earn rewards only when they find valid vulnerabilities. Penetration testers, on the other hand, are hired by companies under contracts and are paid a fixed salary or project fee to test systems for security weaknesses, regardless of how many vulnerabilities they find.

Which is better for beginners: bug bounty hunting or penetration testing?

Beginners often start with bug bounty hunting because it is easier to enter without formal job requirements. It helps build practical skills, real-world experience, and a public track record. Penetration testing usually requires stronger fundamentals, structured training, and sometimes certifications to get hired.

Can you earn a full-time income from bug bounty hunting?

Yes, experienced bug bounty hunters can earn a full-time income. However, income is not guaranteed and can vary widely depending on skill level, consistency, and the quality of vulnerabilities discovered. Many beginners start part-time and transition to full-time after gaining experience.

Do penetration testers need certifications?

Certifications are not always mandatory, but they significantly improve job opportunities. Popular certifications like CEH, OSCP, and CompTIA Security+ help demonstrate skills and increase credibility when applying for penetration testing roles.

What skills are required for bug bounty hunting and penetration testing?

Both roles require knowledge of web application security, networking basics, common vulnerabilities like XSS and SQL injection, and familiarity with tools such as Burp Suite and Nmap. Programming knowledge in languages like Python or JavaScript is also helpful.

Is bug bounty hunting legal?

Yes, bug bounty hunting is legal when done through authorized programs. Companies provide clear rules and scope defining what systems can be tested. Testing outside these authorized programs without permission is illegal.

How do companies benefit from bug bounty programs?

Bug bounty programs help companies identify security vulnerabilities before attackers exploit them. This reduces the risk of data breaches, financial losses, and damage to their reputation.

Can bug bounty hunting help you become a penetration tester?

Yes, bug bounty hunting is an excellent way to build practical skills and demonstrate real-world experience. Many penetration testers use their bug bounty achievements to showcase their abilities and secure professional roles.

What tools are commonly used in bug bounty hunting and penetration testing?

Common tools include Burp Suite for web testing, Nmap for network scanning, Wireshark for packet analysis, Metasploit for exploitation, and Nuclei for automated vulnerability scanning. These tools help identify and analyze security weaknesses.

Which career offers better job stability?

Penetration testing offers better job stability because it provides a fixed salary, regular projects, and employee benefits. Bug bounty hunting offers more flexibility and higher earning potential but comes with unpredictable income.