Table of Contents

Imagine yourself in a trendy café in Hamburg, receiving your coffee perfectly tailored to your preferences, having a conversation with the barista about the raining weather, and understanding her response. At that moment, German ceases to be a subject to study and begins to be a language to live. And the best part is that this reality is not far away.

Complete beginners have gone from zero to passing the Goethe A1 exam in about six months. Some manage it in two to four months with intensive daily practice. They aren’t language prodigies. The majority have full time jobs, families, or school obligations. They differ not in talent but in consistency, smart study choices, and the ability to stick with it when der, die, and das try their patience.

Learn German language in your own language! Get free Demo Classes Here!

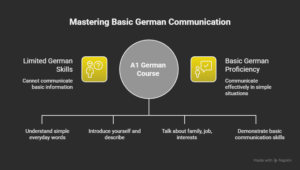

What German A1 Actually Means

The A1 level on the CEFR scale, developed by the Council of Europe, is the starting point in this journey to the German language. At this level, learners are not expected to speak fluently or use complex vocabulary. Rather, the emphasis is on grasping and using simple words of everyday life to convey mundane matters adequately.

At the A1 level, learners can introduce themselves and provide certain personal information. For instance, they can say their name, country of origin, country of residence, e.g., “Ich heiße Sravan, ich komme aus Indien.” Students can also communicate about familiar topics, such as family, job, hobbies, languages spoken, and preferences for food. Conversations are brief, slow, and focused on familiar topics, which makes them easier to comprehend.

Can You Really Reach A1 in Just 6 Months?

1: How do you say "Good Morning" in German?

Many people have passed the Goethe A1 level faster than they hope. On forums like Reddit, you’ll find students who passed the exam within two months of signing up for Duolingo and speaking regularly. Others live for four or six months, working full time and studying in the evening. In reality, six months is a long time for a motivated beginner. It is a test of foundational skills not advanced grammar at the A1 level. Expect to learn about 650 to 800 common words, use simple present tense, some simple questions, and a few clear sentences. There is no need for witty past tenses or sophisticated grammar at this point.

Language learning can only grow over time. The words become more familiar to the brain, the sentences feel more natural, and you learn to be more attentive as your ears begin to adjust to German rhythms. Small daily efforts quickly build confidence.

Free German A1 Mock Tests – Powered by AI!

Test your skills on our interactive platform. Get instant feedback from our AI to help you communicate better and track your progress. Start your free German mock test now.

Test Your German A1 for FreeWhat the A1 Level Really Feels Like

At the A1 level, the focus is on learning language that can be spoken right from the outset. The emphasis is not on mastering complicated rules but on communicating clearly and naturally. Learners come across useful phrases for real-life situations and gain confidence as they begin to make themselves understood.

Learning commences through day-to-day social exchanges—greetings upon arrival and departure, self-introduction, posing straightforward questions, and providing plausible answers. Students practice counting money at a bakery, ordering food, and describing their daily routines. Instead of causing trepidation, phrases such as “Ich stehe um sieben Uhr auf” begin to sound natural. Stating one’s likes and dislikes, “Ich mag Fußball,” takes on ease without angst over grammatical complexities.

Grammar is still simple and manageable at this point. Students learn the present tense and some important verbs like sein, haben, essen, wohnen. They learn some basic concepts like articles and simple negation, e.g., “Ich habe kein Auto.” The goal is clarity and confidence, not perfection.

|

German A2 Exercises – Download Free PDF |

||

The Four Skills the Exam Tests

In all of the tests, learners show their ability to use German in authentic situations by listening, reading, writing, and speaking. The language skills are interrelated and support one another in communication.

Listening: Short everyday audio clips are played, such as someone giving directions, a phone call, or a store announcement. Simple questions are asked about who, what, where, and when.

Reading. Short texts such as messages, signs, advertisements, or notes are provided. The task is to find key information like times, prices, and names.

Writing: Tasks include filling out forms, writing a short postcard or email (30–50 words), or describing a picture. The focus is on clear sentences and correct basics, especially proper noun capitalization.

Speaking: This is usually done with another candidate. Tasks include introducing oneself, asking and answering questions, and role-plays such as ordering food or asking for directions. The main focus is on being understandable, polite, and making an effort to communicate.

Practicing all four skills together will help build your confidence and prevent any surprises on test day.

Quick Look at the Exam Format

It is about 65–80 minutes long and it’s pretty straight forward once you get used to it.

- Listening 20 min 15 questions on 3 audio parts.

- Reading: 30 min, 15 tests on short texts.

- Writing: 20 min; 2–3 short tasks.

- Speaking: 15 min in pairs—self-intro, Q&A, simple role-play.

Must score 60/100 to pass. The test is the same across the globe, so most of the stress is avoided by trying to perform official model tests.

|

Goethe 2026 Exam Dates: Multiple Test Centers |

|

| Trivandrum Goethe Exam Dates | Kochi Goethe Exam Dates |

| Chennai Goethe Exam Dates | Coimbatore Goethe Exam Dates |

Your 6-Month Roadmap (Realistic & Flexible)

This plan builds gently so you don’t burn out. Adjust if life gets busy, but try to stay consistent.

Month 1: Get Comfortable with Sounds & Basics

Learn the letters of the alphabet (ä, ö, ü, ß), nail the sounds of hard and soft (“ch” in a rolled form, rolled r), and learn survival phrases— greetings, numbers 1–20, days, “Ich heiße …”, “Wo ist…?” Label things at home, listen to slow music, sing everything out loud. Goal: greet people, share basic facts, but not freezing.

Month 2: Grammar Foundations + Word Building

Take off der/die/das, ein/eine, present tense verbs, simple questions/negatives. Build vocab in themes (family, colors, food, clothes). Daily write down and say short sentences (“Meine Mutter wohnt in…”, “Ich esse gerne Reis”). Use flash cards + mini-stories. Goal: Write the basic sentences easily.

Month 3: Start Talking & String Sentences Together

Focus on full sentences, verb order (verb second), describing routines/hobbies. Talk every day—narrate your morning, play shopping, write notes. If possible, find a language partner. The goal: Have 2–3 minute chats with fewer pauses.

Month 4: Train Your Ear & Eyes

Read real beginner texts (menus, emails, signs); listen slow podcasts/songs/dialogues. Replay, shadow speakers, note new phrases. Object: to be able to enjoy simple authentic content without panic.

Month 5: Test Yourself & Fix Gaps

Be able to take weekly full-time practice exams. Review mistakes and correct weak topics (articles, verbs, pronunciation). Goal: Increase stamina and confidence while in battle.

Month 6: Polish & Get Mentally Ready

More mocks, more speaking practice, review key phrases/grammar. Work on slow breathing and positive thinking. Goal: walk in prepared and excited.

Free German A1 Mock Tests – Powered by AI!

Test your skills on our interactive platform. Get instant feedback from our AI to help you communicate better and track your progress. Start your free German mock test now.

Test Your German A1 for FreeSimple 1-Hour Daily Routine That Actually Works

Keep it sustainable:

- 20 min vocab: review old + learn 10–15 new in sentences (flashcards/apps).

- 20 min grammar: one rule + exercises + write your own examples.

- 20 min listening/speaking: play audio, repeat aloud, answer questions, describe what you heard.

Short, focused, every day > long cramming sessions.

Resources That Real Learners Swear By

Apps

Duolingo (fun, habit-forming), Babbel (great for conversations + pronunciation feedback), Memrise (spaced repetition for vocab).

Videos

Easy German (real interviews with subtitles—feels like hanging out with friends), Deutsch für Euch (clear explanations), Nicos Weg (story-based, addictive).

Books & Practice

Netzwerk A1 or Menschen A1 (textbook + audio), Goethe-Institut free model tests, Hueber Fit fürs Zertifikat A1 (exam-focused drills).

Mistakes I’ve Seen People Make (Don’t Do These)

- Memorizing lists without speaking → words vanish fast; use them in sentences/talks.

- Avoiding speaking practice → reading feels good but speaking stays scary—talk daily, even to yourself.

- Studying only when motivated → inconsistency kills progress; make it a non-negotiable habit.

Exam Day – Little Things That Help

- Pace yourself—don’t get stuck; mark and return.

- In speaking: breathe, smile, speak clearly, don’t rush. Examiners want to understand you—they’re not trying to trick you.

Learn German language in your own language! Get free Demo Classes Here!

Wrapping Up

Six months is a reasonable and significant target to achieve the A1 language proficiency level, and accomplishing this can positively impact one’s life. Learning a language involves more than recalling vocabulary or grammar rules; it engages the mind in novel cognitive processes, instills confidence, and equips you with the ability to engage with new people and cultures. While it may not be effortless, dedicating six months of consistent work can yield substantial results. This won’t be a quick process—but it will be a rewarding one. Some days, the rules of grammar will be perplexing or strange, or new articles will make no sense to you. You may have to read the same lesson multiple times and still feel baffled. Every student goes through this. Your frustration does not mean you are failing; in fact, frustration often means that your brain is changing and growing.

Free German A1 Mock Tests – Powered by AI!

Test your skills on our interactive platform. Get instant feedback from our AI to help you communicate better and track your progress. Start your free German mock test now.

Test Your German A1 for FreeFrequently Asked Questions

Is It Really Possible to Pass the Goethe A1 Exam in Just Six Months If I Work a Full-Time Job?

The short answer is yes, and thousands of successful learners have done precisely that. However, the longer, more honest answer requires unpacking what “possible” actually means in the context of your life, your current responsibilities, and your relationship with language learning.

What Specific Vocabulary and Grammar Topics Must I Master for the A1 Exam?

The Goethe A1 examination is not an open-ended test of everything German. It is a tightly defined, predictable assessment of foundational language skills, and understanding its precise boundaries is the difference between studying efficiently and drowning in unnecessary detail.

How Should I Divide My Study Time Across Listening, Reading, Writing, and Speaking?

The most common mistake beginners make is studying German as if it were a dead language—something to be analyzed on paper rather than lived in the mouth and ear. They spend hours highlighting grammar rules, completing workbook exercises, and memorizing vocabulary lists, yet they freeze when a native speaker asks them a simple question.

Which Resources and Textbooks Are Most Effective for Self-Study A1 Preparation?

Navigating the overwhelming landscape of German learning resources is itself a skill that many beginners underestimate. There are dozens of textbooks, hundreds of apps, and thousands of YouTube channels all claiming to be the fastest path to fluency.

How Do I Stay Motivated and Consistent When I Feel Discouraged or Overwhelmed?

Motivation is not a personality trait that some possess and others lack. It is an emotional state that fluctuates naturally, predictably, and universally among language learners. The difference between those who reach A1 in six months and those who abandon the attempt after six weeks is not that the successful learners never felt discouraged.

What Is the Goethe A1 Exam Format, and How Can I Avoid Surprises on Test Day?

The Goethe-Zertifikat A1: Start Deutsch 1 is a meticulously standardized examination administered at Goethe-Institut locations worldwide, and its predictability is your greatest strategic advantage. This is not an exam designed to surprise or confuse candidates.

How Important Is Pronunciation and Accent at the A1 Level?

Pronunciation occupies a paradoxical position in beginner German. It is simultaneously one of the most neglected skills and one of the most consequential for both exam success and real-world communication.

Can I Pass A1 Using Only Free Resources, or Do I Need Paid Courses and Tutors?

The democratization of language learning resources over the past decade has fundamentally altered what is possible for self-directed learners. Twenty years ago, motivated beginners without access to formal instruction faced significant barriers.

What Happens If I Fail the Exam? Can I Retake It, and How Should I Adjust My Approach?

The fear of failure prevents more language progress than any grammatical concept ever invented. Learners invest so much emotional energy in the possibility of not passing that they cannot fully invest in the process of learning.

What Does Life After A1 Look Like, and How Do I Continue to A2 and Beyond?

Passing the Goethe A1 examination is a genuine achievement, and you should celebrate it fully before immediately pivoting to the next goal. You have demonstrated to yourself and to an accredited institution that you can function in basic German.