Table of Contents

Imagine the scene: You walk into a bright, quiet room, three years olds pour water from tiny pitchers, four year olds sort colourful beads by size, and five year olds quietly read simple words they have made themselves. No one shouts directions. No bells ring to switch activities. Children decide what draws them in, and they keep it going longer than you’d think. That quiet, focused scene is the heart of Montessori instruction, and it draws so many to become preschool teachers in these schools.

But getting the job means that it will be interviewed to answer more than a standard teaching question. Schools want to know how you get the Montessori way, not just the ideas, but the reasons. They look for somebody to make that special atmosphere every day. This guide lists the top 20 Montessori interview questions for preschool teachers. It is complete with clear explanations, realistic examples and tips for walking in ready and confident. Continue to read the letter straight through and you will be ready to explain why you are in a Montessori classroom. You can turn an interview good into the moment a school says, “This is the person we need.”

Register for the Entri Elevate Montessori Teacher Training Program! Click here to join!

What is the Montessori Teaching Method?

Maria Montessori started this approach more than a century ago while working with children in Rome. As a doctor, she watched how kids naturally learned when given freedom to explore. She noticed they concentrated deeply on tasks they picked themselves, especially when the tools matched their current stage of growth. That observation became the foundation of everything.

In a Montessori preschool, the classroom feels like a thoughtfully designed home for young minds. Low shelves hold beautiful, child-sized materials arranged in clear order. A child can walk over, take a tray of knobbed cylinders, carry it carefully to a mat, and work on fitting shapes until satisfied. No adult hovers or corrects every move. The teacher shows how something works once, then steps back.

Ideas Behind the Method

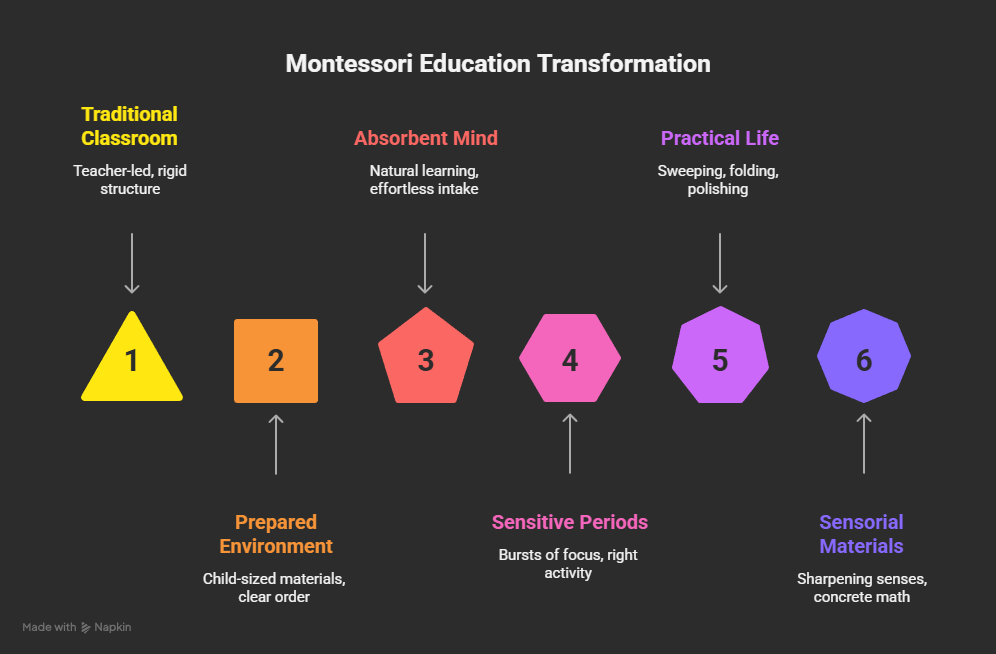

The method rests on a few big ideas. First, respect the child as an individual with their own timing and interests. Second, recognize the “absorbent mind”—that amazing ability in the first six years where children take in everything around them like little sponges, building language, movement, and understanding without effort. Third, watch for sensitive periods, those bursts of strong focus on things like order, tiny details, or words. When a child shows one, the right activity appears at just the right moment.

Practical life exercises occupy a large part of the day. Children learn to sweep, fold cloths, polish shoes, or prepare fruit snacks. These tasks build coordination, independence, and pride in doing real work. Sensorial materials sharpen the senses—smelling jars, feeling different textures, grading colors. Math starts with concrete objects: golden beads show place value, number rods teach length and quantity. Language grows through sandpaper letters which children trace with their fingers, then movable alphabets for making words.

Mixed-age groups (usually three to six years old) create natural community. Older children help younger ones, which reinforces their own knowledge and builds kindness.

Teaching Principles

Montessori teachers rely on gentle patience and careful observation. Rather than directing a child at every turn, they watch and get to know each child with their own unique personality and talents. They make note of a child’s interests and stages of skill development, and particularly of when the child is ready for a new challenge. These observations allow the guide to know when and how to offer the proper lesson at the proper time. Montessori training prepares guides in the art and science of prepared environment, of offering lessons and materials in a calm and respectful manner, and of managing their classroom with confidence and care.

Why Interviewers Ask Montessori-Specific Questions

1: What is the primary focus of the first plane of development in the Montessori method?

Montessori schools stand out from the rest because the whole philosophy is woven into every aspect – from the height of the furniture to how you deal with conflicts that inevitably pop up.

When you’re answering these questions it says a lot about how you think about discipline, progress and getting parents on board in this kind of setting. A candidate who shows they prevent problems by keeping kids engaged in their work and not relying on rules & punishments – that’s a sign of a strong teacher. It shows you value independence and know how to nudge kids gently in the right direction.

Good responses build trust with the panel super fast. When you share your knowledge or some personal experience from your classroom time, the panel gets a clear picture of you as a teacher who will keep the Montessori environment safe and help every kid who steps into your room really thrive. And in this field where having lots of passion is just as important as having the skills, answers like that can really help you stand out from the crowd and show you’re a good long-term fit for the school.

If you put in the effort to get your thinking straight, the benefits go way beyond just getting the job. You’ll really get to the heart of why you’re into this kind of work to begin with. All of a sudden your enthusiasm will shine through and that might just be the thing that tips the scales in your favour. Schools protect their programs by hiring the right teachers to carry out their vision – and if you can nail these questions you’ll show you’re able to hit the ground running & be a vital part of the team from day one.

Get Certified & Start Your Montessori Career

Montessori Teacher Training Course by Entri App: Gain expert skills, earn certification, and kickstart your teaching career.

Join Now!Top 20 Montessori Interview Questions for Preschool Teachers

These are asked repeatedly because they really get to the heart of Montessori. Below each question you will find an explanation of why it gets asked, a sample answer that sounds natural, and tips to help you form your own authentic and effective responses. Practice saying them aloud. Allow your genuine enthusiasm to shine through.

1. Describe your understanding of the Montessori philosophy.

Interviewers begin here to assess your foundation. They want more than rote-remembered facts; they want to hear you speak.

Sample answer: Montessori has always seemed to me to be about recognizing a very young, interested person and setting them on their own path of discovery in a safe and managed environment. It involves setting up the environment and gently coaching the individual child toward independence, concentration, and respect for themselves and others through hands on experiences that are developmentally appropriate.

Tips: Talk from the heart. Mention the one or two of your top 3 values. Keep it warm but clear so they sense your belief.

2. How would you set up a Montessori classroom for pre-schoolers?

This checks whether you know how to make the space work for children, not adults.

Sample answer: I will provide low shelves which contain trays with inviting materials arranged by area—practical life near the entrance, sensorial materials placed in the middle followed by math and language objects at the back of the room. Materials will be kept neat and complete to allow the children to have a sense of autonomy. Living plants, soft natural lighting and child-sized tables and chairs will create a serene inviting atmosphere that triggers a desire to discover.

Tips: Paint a picture with details. Explain why choices matter (accessibility builds confidence, beauty keeps interest high).

3. Explain the role of observation in Montessori teaching.

Observation is the teacher’s main tool. This question tests if you see its power.

Sample answer: Observation lets me really know each child—what captures their attention, what frustrates them, when they repeat an activity over and over. I sit quietly, take notes, and use those insights to decide when to present a new lesson or adjust the shelves. It helps me follow the child instead of pushing my own plan.

Tips: Share a short example from experience or training. Show how observation leads to better support.

4. How do you handle discipline in a Montessori classroom?

Here, they look for an approach rooted in respect, not control.

Sample answer: I focus on prevention through engaging tasks and clear expectations. When problems arise, I remain calm, position myself at the child’s level, and guide them to understand the impact of their behavior. We might practice the right way together or find a logical consequence, like helping clean up a mess. The goal is always building self-discipline and kindness.

Tips: Avoid mentioning rewards or harsh consequences. Highlight modelling and redirection.

5. What are sensitive periods, and how do you support them?

This digs into developmental knowledge.

Sample answer: Sensitive periods are those intense phases when children show huge drive toward certain skills—like perfecting order around age three or exploding into language between three and six. I watch for signs, then make sure the right materials are ready and accessible. Offering them at the peak moment helps the child dive in deeply and joyfully.

Tips: Name two or three periods. Connect to excitement and natural mastery.

6. Describe a typical day in your Montessori preschool class.

They want to see you understand the rhythm.

Sample answer: We begin with a short, warm circle for songs and calendar. Then comes a long, uninterrupted work period—three hours where children freely choose activities. Practical life often starts the morning because it grounds everyone. Snack is self-serve. We close with outdoor time, stories, and group clean-up so children feel part of the community.

Tips: Stress child choice and flexibility. Mention how you adapt for the group.

7. How do you incorporate practical life activities?

These build the base for everything else.

Sample answer: Practical life runs through the whole day. Children pour drinks, set tables, wash cloths, arrange flowers. These simple tasks develop focus, fine motor control, and care for the environment. They give a real sense of purpose and help children feel capable in their world.

Tips: List a few favourites. Explain emotional and physical gains.

8. What materials would you use for sensorial education?

This checks familiarity with classic tools.

Sample answer: I rely on favourites like the pink tower for visual size grading, brown stair for dimension, colour boxes for matching shades, and geometric solids for shape exploration. Sound cylinders sharpen hearing, fabric boxes teach touch. Each one isolates a quality so children refine their senses clearly.

Tips: Pick four or five. Briefly say what each teaches.

9. How do you promote language development in Montessori?

Language blooms naturally here.

Sample answer: I talk with children constantly, using rich, precise words. Books stay available everywhere. Sandpaper letters let kids feel sounds while hearing them. The movable alphabet encourages early writing before reading. Group lessons spark conversation and storytelling.

Tips: Tie to the absorbent mind. Show progression from concrete to abstract.

10. Explain the importance of mixed-age classrooms.

This sets Montessori apart.

Sample answer: Mixed ages create a family-like setting. Older children model skills and gain leadership by helping. Younger ones absorb naturally by watching. Everyone learns patience, cooperation, and respect. It also lets each child work at their true level without artificial grade barriers.

Tips: Give a quick story-like example of sibling-like support.

11. How do you assess student progress without tests?

Traditional grading does not fit.

Sample answer: I track through careful observation and detailed records—what work a child chooses, how long they stay focused, what skills they master. Portfolios collect photos and samples. I share these with parents so everyone sees the full picture of growth in academics, social skills, and independence.

Tips: Emphasize respect for pace. Mention how it guides next steps.

12. What challenges have you faced in Montessori teaching, and how did you overcome them?

They want honesty and growth.

Sample answer: I found that one of my four-year-olds was constantly wandering and interrupting others. Upon close observation, I realized that he needed more gross-motor outlets. I assigned him some heavy work outside and filled a special tray with some challenging practical tasks. Within a few days, his concentration improved and the entire atmosphere of the room became calmer.

Tips: Pick a real-sounding issue. Focus on observation and positive change.

13. How do you involve parents in Montessori education?

Partnership matters.

Sample answer: I invite parents to observation mornings so they see the method in action. We hold workshops on extending activities at home—like child-sized tools for chores. Regular notes and chats keep communication open so school and home feel consistent.

Tips: Stress mutual learning. Give examples of trust-building.

14. Describe how you use nature in your teaching.

Montessori favors the real world.

We go outside every day to collect leaves, watch insects, water plants. We bring seasonal finds in to put on our indoor nature tables for sorting and naming. Gardening is a practice that teaches patience and cycles. All of these experiences help to ground abstract ideas in living things that the children can touch and care for.

Remember to include safety and wonder.

15. How do you handle a child who resists activities?

Resistance often signifies a deeper attachment.

Sample answer: I first try to observe to find out why the child says no—perhaps they find the activity challenging or they just need to feel connected to me. I might offer the child some choices within a certain framework or offer something similar but more appealing. Spending time with the child, just the two of us, usually renews their interest in participating without any coercion.

Tips: Show empathy and patience.

16. What role does art play in Montessori?

Creativity has its place.

Sample answer: Art stays open-ended—crayons, clay, collage materials always ready. Children create freely without templates. We connect it to other areas, like drawing plants after a nature walk. The focus stays on process and expression, which supports fine motor growth and imagination.

Tips: Downplay product focus.

17. How do you teach math concepts Montessori-style?

Concrete before abstract is key.

Sample answer: We start hands-on: number rods show quantity, sandpaper numbers teach symbols, golden beads build place value. Children manipulate materials until concepts feel solid, then move to paper work naturally. Discovery stays joyful.

Tips: Walk through sequence briefly.

18. What is normalization in Montessori, and how do you achieve it?

This describes the ideal state.

Sample answer: Normalization looks like deep concentration, kindness, and joyful work across the room. I help it happen with consistent routines, beautiful materials that match interests, freedom to choose, and calm modelling. When children feel respected and engaged, the group settles into harmony.

Tips: Describe signs so it feels vivid.

19. How do you adapt Montessori for children with special needs?

Inclusion fits the philosophy.

Sample answer: I observe strengths and challenges closely, then adjust materials—like bigger handles for grip issues or quieter corners for sensory needs. I work with families and specialists while keeping the child-led spirit. Every child deserves the chance to grow at their pace.

Tips: Focus on possibilities.

Register for the Entri Elevate Montessori Teacher Training Program! Click here to join!

20. Why do you want to teach in a Montessori school?

This shows your drive.

Examples of answer: I love watching children light up when they master something on their own terms. Montessori lets me navigate without pushing, support without pushing. The idea of seeing confident, curious kids develop into thoughtful people fills me every day with purpose.

Tips: Take it seriously, personal and real.

Parting Words

You now have your complete toolkit of Montessori interview questions. Reflect on your own experiences and learn to say these answers in your own words. When you speak authentically, and with warmth, schools see not just a qualified teacher, but a person willing to nurture their communities. Be prepared – you can make a difference.

Get Certified & Start Your Montessori Career

Montessori Teacher Training Course by Entri App: Gain expert skills, earn certification, and kickstart your teaching career.

Join Now!Frequently Asked Questions

What qualifications do you need to become a Montessori preschool teacher?

Most schools expect a recognized Montessori certification for the 3–6 age group, along with a basic degree in any field. Training programs based on the principles developed by Maria Montessori prepare you to understand child development, classroom materials, and observation techniques. Some schools also prefer prior classroom or internship experience.

How is a Montessori teacher interview different from a regular preschool interview?

Montessori interviews focus less on classroom control and more on observation, independence, and child-led learning. Interviewers want to know how you prepare the environment, present materials, and guide children without constant instruction. They also assess your understanding of Montessori philosophy, not just teaching skills.

Do you need teaching experience before attending a Montessori interview?

Experience helps, but it is not always mandatory. Schools value candidates who show clear understanding of Montessori principles, strong observation skills, patience, and genuine respect for children. Even candidates with training but limited experience can succeed if they explain the method clearly and confidently.

What are the most important Montessori concepts to prepare before an interview?

You should understand key concepts such as the prepared environment, absorbent mind, sensitive periods, normalization, mixed-age classrooms, and practical life activities. Interviewers often ask questions related to these ideas to evaluate your depth of knowledge.

Why is observation so important in Montessori teaching?

Observation helps teachers understand each child’s interests, readiness, and challenges. Instead of forcing lessons, teachers use observation to introduce the right activity at the right time. This supports natural learning and builds concentration and independence.

How should you answer Montessori interview questions if you are a fresher?

Focus on your training, understanding of Montessori philosophy, and your attitude toward children. Use examples from your coursework, practice sessions, or internships. Schools value mindset and clarity, not just years of experience.

What mistakes should you avoid during a Montessori teacher interview?

Avoid talking about rewards, punishments, or controlling children strictly. Montessori education focuses on self-discipline and guidance, not authority. Also avoid giving memorized answers without showing genuine understanding.

How can you demonstrate your Montessori knowledge during the interview?

Explain concepts in simple words, give real examples, and describe classroom situations. For example, explain how you would present a material, observe a child, or handle a conflict calmly and respectfully.

Do Montessori interviews include practical demonstrations?

Some schools may ask you to demonstrate how you present a Montessori material, such as pouring, sandpaper letters, or number rods. This helps them evaluate your calmness, clarity, and respect for the learning process.

How can you prepare effectively for a Montessori preschool teacher interview?

Study Montessori principles, review common interview questions, and reflect on your own experiences with children. Practice explaining concepts clearly and naturally. Confidence, clarity, and genuine respect for child development make the strongest impression.